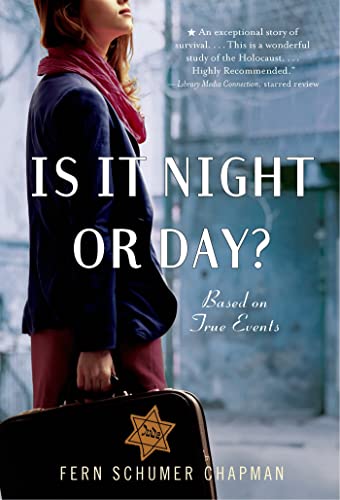

Items related to Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival,...

It's 1938, and twelve-year-old Edith is about to move from the tiny German village she's lived in all her life to a place that seems as foreign as the moon: Chicago, Illinois. And she will be doing it alone. This dramatic and chilling novel about one girl's escape from Hitler's Germany was inspired by the experiences of the author's mother, one of twelve hundred children rescued by Americans as part of the One Thousand Children project.

This title has Common Core connections.

Is It Night or Day? is a 2011 Bank Street Best Children's Book of the Year.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1

NOBODY TOLD ME ANYTHING

Germany 1938

The first long train trip I ever took in Germany was my last. Now I see that it was a funeral procession. The mourners traveling with me were my father, my mother, and Mina, a Christian girl who lived with my family and was as dear to me as my big sister, Betty. We were burying my childhood.

The train would take us from our little town of Stockstadt am Rhein all the way to Bremen, about 320 kilometers (200 miles) away. Only once had I been so far away from home: a year earlier, my parents had borrowed our uncle’s car, and we had taken Betty to the Bremen port to see her off when she left for America. Until then, I had never even ridden my bike farther than the next town. From that trip with Betty and from my geography class, I knew that Bremen was a big city, a port where huge ships came and went, day and night. Soon I would board one of those ships and sail to America, all by myself.

Chicago. I was going to Chicago, the city where Betty now lived with her new family. We had not studied that place in my geography class. But I knew from her address that Chicago was in a state called Illinois. I didn’t even know what a state was, but I knew Illinois was in this distant place called America, which my father sometimes called das gelobte Land, "the promised land." It felt like I was going to the moon.

"Show me your passport." My father’s voice broke through my thoughts as I stared out the train’s window. The wheels screeched, steam puffing up off the tracks. Without taking my gaze from the window, I held up the passport dangling from a string around my neck. We all jerked backward as the train began to move. The local church, our school, my house on Rheinfeldstrasse, drifted past us, each a perfect postcard. The train picked up speed: the pictures blurred.

My father was still talking. "Now, Tiddy, your ticket is right here, too," he said, patting the breast pocket of his best wool coat. "You remember, we’re sending a telegram to Onkel Jakob, your uncle in America. The Jewish group organizing the trip will let him know when to meet you. In Chicago, yes? Tiddy?"

Onkel Jakob? I’d never met Onkel Jakob. How would I know him when I saw him? I certainly couldn’t ask anyone, since I couldn’t speak English. And Onkel Jakob, who went to America nearly thirty years ago—would he still speak German?

I knew only one story about this Onkel, my father’s eldest brother, who had emigrated in 1910. My father had told me that Jakob enlisted in the ambulance corps, not the infantry, in the United States Army. He feared that if he served in the infantry, he might find himself pointing a gun at the head of one of his two brothers serving on the German side.

His youngest brother, my father, Siegmund, was proud to have served the Fatherland in the Great War and proud of the medal he’d won—the famous Iron Cross, trimmed in white, with the year 1914 engraved on its face. Captured by the Russians and held as a prisoner of war, he learned to speak Russian. That made him fluent in five languages.

My father believed absolutely in Germany, and so he was stunned by the anti-Semitism that swept the country in the 1930s. "I can’t believe my comrades would turn against me," he often muttered as he fingered the Iron Cross that was displayed on a bookshelf in our living room.

His ancestors—my ancestors—had been among the town’s original settlers. The old records showed that the Westerfelds had lived in Stockstadt long before Germany was Germany, for more than two hundred years. My parents had told me that we were descended from refugees who had fled the Spanish Inquisition and settled—a few families here, a few families there—in the towns and cities of northern Europe. Only one other Jewish family, my mother’s ancestors, came to Stockstadt. Their descendants, my mother’s cousins, had fled to America a few years ago, when things started to get bad for Jews. After my parents sent my sister away, only four Jews—my mother, my father, my grandmother, and I—were left in the town of two thousand people.

I’d often heard my parents talk about how Hitler urged towns to make themselves "free of Jews." Now, a large sign in front of a village hall caught my eye as the train sped past. Judenfrei, it said. That town had met its goal.

But not in our town. In Stockstadt, there would still be three.

Why hadn’t we all left together? Months, then years, had slipped away as my parents tried to decide what we should do. My mother wanted the whole family to emigrate together, but my father couldn’t persuade his mother, who lived with us, to leave. In 1721, the Westerfelds had built our home, a large German Tudor held together with straw and manure, and carefully maintained and handed down from one generation to the next. My father’s mother, Oma Sarah, often reminded us that this was her home; she had always lived within these walls, this town, this country.

"I was born a German," she would tell my father whenever he pressed her to leave, "and I will die a German."

My father wouldn’t go without his mother. For the longest time, he thought that things eventually would change in Germany and, he’d say, things really weren’t too bad. As long as the laws weren’t too restrictive, as long as he could bring in money by buying and selling local produce, as long as he could believe that Hitler wouldn’t last, he could wait. "Der Vierer geht, aber der Fünfer kommt," he’d say: "The year ’34 is going away, but ’35 is coming." In German, it was a pun that suggested the Führer, Hitler, would be gone.

Still, my father didn’t want to take any chances with his daughters. He and my mother debated endlessly, weighing my sister’s and my safety in Germany against an unknown life in a foreign country without them. How could children survive thousands of miles away from their mother and father? He couldn’t bear that thought, so he filed the papers for passports and permission for all of us to emigrate together, hoping that Oma Sarah, who never changed her mind about anything, might consider leaving the only home she and her Westerfeld ancestors ever knew.

The day my father nearly "died a German," he realized things were much worse than he had thought. He had gone to the tavern across the street from our house. Often, after work, he would have a beer with some of our Stockstadt neighbors. As he walked in that evening, a group of rowdy men—many of them my father’s customers, and some his grammar school classmates—were clanking beer steins and singing loudly. Several turned to face my father, stuck out their arms, and said "Heil Hitler," and burst into the Nazi national anthem, "Das Deutschlandlied."

My father, whom Betty and I called Vati, turned and left. But a few men followed, chasing him into our main street, Rheinfeldstrasse. He ducked into the stairwell at the village hall, hoping to lose them, but they saw where he went. He struggled, pushing against the glass door to keep it closed. The men counted together, Eins, zwei, drei, then heaved, shoving the door open. Vati was trapped. Calling him dreckiger Jude—"filthy Jew"—the men kicked and beat him until he lost consciousness.

Some time later—he had no idea how long—with swollen eyes, purplish lips, and a bloody nose dripping onto his blue-and-white-checked work shirt, he staggered through our front door, smelling of vomit and beer.

"Siegmund!" my mother shrieked, and ran to steady him. "Was ist denn mit dir passiert? What happened to you?"

For a month he lay in bed, recovering from broken ribs, bruised kidneys, and a ruptured spleen. Some days, it seemed he just lay there, staring out the bedroom window all day long. Finally, on the first day he was up and around again, he told my mother that he could see only one solution to the anti-Semitism in Germany. "We must send our daughters to safety in America."

I knew this only from what I saw and what I was able to piece together from bits of conversations I’d overheard. Nobody told me anything. Even when Betty left, no one said much; we behaved as if her trip were just a brief separation, a temporary inconvenience before we would all be together again in America. My parents could not bring themselves to speak of the possibility that we might never see one another again.

Betty was only fourteen then, but she seemed so much older to me. Just before she left, she had lost some of her baby fat, and her thick, dark hair framed her face, showing off her high cheekbones, clear skin, and beautiful brown eyes. I figured if I ever had to go to America, I’d be all right if I could live with Betty! When I told Vati this, he said that he couldn’t necessarily arrange that. "We take what we can get, Tiddy."

Now they were sending me away and, though Betty and I would be in the same city, I was going to live with relatives, many miles from my sister, who was living with a foster family my parents and I didn’t know. That family had agreed to take in Betty as a companion for their only daughter.

On the train, my father was saying, "When you get to Chicago, Tiddy, see how you might raise some money so that we can join you." Until recently, money hadn’t been a problem for our family. But in the last few years it had become difficult for my father to make a living and he had spent most of his savings on passports, tickets, and bribes to get Betty and me out of Germany.

I turned to face him. "Your Onkel Jakob will help you send us the money," he continued.

I stared hard, scarcely listening, working instead to photograph my father’s face in my mind, so I would always remember him. He was just forty-three, but he looked ancient. His deep brown eyes never sparkled anymore. It had been months since I’d seen the fine net of tiny ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSquare Fish

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1250044219

- ISBN 13 9781250044211

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival, 1938-1942

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1250044219

Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival, 1938-1942

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1250044219

Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival, 1938-1942

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1250044219

Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival, 1938-1942

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1250044219

Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival, 1938-1942

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1250044219

Is It Night or Day?: A Novel of Immigration and Survival, 1938-1942

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1250044219

Is It Night or Day?

Book Description Condition: new. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. Seller Inventory # PSN1250044219