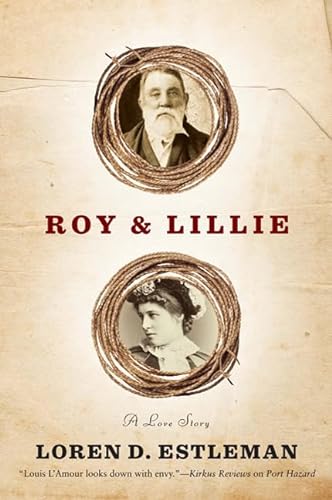

Items related to Roy & Lillie: A Love Story

A unique novel of England and the Old West

Roy was Judge Roy Bean, the infamous, notorious real-life Justice of the Peace whose life has been the source of biographies, novels, plays, and films. Lillie was Lillie Langtry, the celebrated “Jersey Lily” of the British stage. They never met, but they wrote letters to each other. From very different backgrounds, living vastly different lives, separated by an ocean and most of a continent, these two unforgettable people share something unique in the “lost letters” of this novel. For many years Bean, the cantankerous self-styled arbiter of rough frontier justice, wrote fan letters to the beautiful actress across the sea; occasionally, she wrote back. He even renamed the town in which he lived Langtry in her honor. And they would have met, if Bean had not died shortly before Lillie, after years of this strange but poignant correspondence, finally kept her promise to visit her distant admirer.

In this story of letters lost, Loren D. Estleman, with all the nuance and narrative skill that has won him multiple Spur Awards, brings to life an untold chapter of transatlantic love that is as tender as it is unique.

Roy was Judge Roy Bean, the infamous, notorious real-life Justice of the Peace whose life has been the source of biographies, novels, plays, and films. Lillie was Lillie Langtry, the celebrated “Jersey Lily” of the British stage. They never met, but they wrote letters to each other. From very different backgrounds, living vastly different lives, separated by an ocean and most of a continent, these two unforgettable people share something unique in the “lost letters” of this novel. For many years Bean, the cantankerous self-styled arbiter of rough frontier justice, wrote fan letters to the beautiful actress across the sea; occasionally, she wrote back. He even renamed the town in which he lived Langtry in her honor. And they would have met, if Bean had not died shortly before Lillie, after years of this strange but poignant correspondence, finally kept her promise to visit her distant admirer.

In this story of letters lost, Loren D. Estleman, with all the nuance and narrative skill that has won him multiple Spur Awards, brings to life an untold chapter of transatlantic love that is as tender as it is unique.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

LOREN D. ESTLEMAN is the winner of multiple awards for his western writing, including five Spurs, two Stirrups, and three Western Heritage Awards. He lives in Central Michigan with his wife, author Deborah Morgan.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

ONE

His reputation, like the lust for Stetsons and high-heeled boots, started at the state line, and he made the most of it by plastering the front of the Jersey Lilly with signs (ICE-COLD BEER & LAW WEST OF THE PECOS) and placing himself on display in a rocking chair on the porch at train time. Earlier he’d bribed conductors and porters to prime passengers for the big attraction, but the railroad men were willing enough to spread the stories free of charge, so eventually he returned his poke to his pocket. Roy was scrupulous when it came to his own money.

Pilgrims who witnessed this exhibition of living waxworks noted that physically, the man matched his legend, and assumed he was born fully fleshed out in his seventh decade, with his belly spilling through the banker’s waistcoat buttoned only at the top, tumbleweed whiskers, and eyes that glistened like damp plums under a sombrero with a buggy-wheel brim. But in his youth he was a frontier Apollo, tall and rawboned, with a bristling black beard; a land-locked Pirate Prince who shot a man in San Diego, California, over an affair of the heart and spent his period of incarceration accumulating poundage from a steady supply of cold chicken and enchiladas smuggled into his cell by pretty señoritas of the old pueblo. In Roy Bean’s universe, a pirate was never anything less than a prince and señoritas were invariably pretty.

Was this man, loose-gutted and musty-smelling, the lean young panther who’d crouched behind bars, fastidiously licking grease from his fingers and grinning at the giggling spectators outside?

“I have an old injury from a fall from my horse while serving with the U.S. Cavalry during the battle for Mexico City,” he wrote Lillie Langtry many years later, by way of one of his literate children. “The pettifoggers in Washington have held up my pension, but there is one less Spanish despot walking the earth for my effort, and that’s sufficient reward.”

He was anticipating a face-to-face meeting with the actress and the need to explain the stiff neck that had plagued him for nearly fifty years. The complaint was actually the result of a lynching that failed to take. He’d cultivated the facial hair, it was said, to mask the hemp scars. The circumstances were cloudy but had something to do with the honor of a young woman. (A pattern was forming.) It happened— if it happened— in Los Angeles, California, more than six years after the ratification of the peace treaty between the United States and Mexico.

He never defended the Union, and his subsequent attempt to bring it down at Glorieta was neglibile. In the last year of the Mexican adventure, most accounts place Roy in Independence, Missouri, with his brother Sam (who had served with the American expeditionary force below the border), arranging to join a wagon train with the intention of establishing a trading post west of the Rockies. Roy was always an entrepreneur first, a colorful character second, and a man of justice only because he refused to relinquish possession of the only book on Texas statutes for two hundred dusty miles.

If, however, he could be said to have come by anything honestly, it was his interest in the disposition of the law. Another brother, Joshua, presided over primitive San Diego as alcalde, a post that settled disputes among natives and passed sentence for capital crimes such as the theft of a neighbor’s sourdough starter. Josh, too, claimed service in Mexico, but no record ever surfaced. He stepped into the more Anglo-sounding office of mayor when American interests prevailed, and in 1850 secured an appointment as general with the California state militia, shooting claim-jumpers from the goldfields and the occasional Chinese. Subordinates with a good sense of an international play on words addressed him as “General Frijol.” As the brother of so prominent a man, Roy basked in reflected esteem, romancing girls in his fine new clothes obtained on Josh’s credit, until he suggested a shooting contest with a rival named Collins— from horse back, with each man presenting himself as the other’s target.

Collins accepted. The combatants made a few galloping passes in jousting fashion, wheeling their panting mounts and firing Paterson revolving pistols across the pommels, while spectators cheered and ducked stray rounds; the challenged party missed his challenger by a Texas mile and fell from the saddle when a ball tore through his leg. Roy drew jail time and the generosity of the Mexican girls with their cornmeal concoctions and baskets of cooked fowl. When he tired of that, his Indian drinking companions freed him with picks and shovels, to the annoyance of the judge, who was proud of the new construction of fieldstone and poured concrete. In a fit of pique he released the recovered Collins from custody.

The melodrama in Los Angeles followed. Roy wrote Lillie: “It was my privilege to slay Joaquin, the legendary highwayman, after he murdered my dear brother Joshua from ambush over a difference of principles.”

He neglected to mention that a friend of the great bandit’s had fallen out with General Frijol over the affections of a young Indian woman and had lain in wait for him with a musket.

All his long life, Roy clung to the quixotic notion that his favorite brother was one of the last victims of the great Joaquin Murietta, or at least of the road agent’s machinations behind the event. It would not do that a barefoot cobbler named Cipriano Sandoval was anything more than the instrument in the passage of a Bean, or that the affair was triggered by nothing more poetic than simple lust. Eventually he may even have come to believe that he was the slayer of Murietta, and not a company of Rangers under the command of Harry Love, a character nearly as colorful as Roy, but one who came without punchlines. Like the prehistoric hunter who wore the skin of the lion he vanquished, Roy adopted the gaudy costume of the New World Spaniard, favoring black sombreros chased with silver, embroidered waistcoats, and tight pantaloons vented at the cuffs and trimmed with bells, until age, girth, and the dignity of public office counseled a more conservative form of dress.

Roy’s only recorded brush with Joaquin was the time he failed to put in top bid for the bandit’s severed head preserved in a pickle jar— presumably as a trophy to support his claim— a failure lamented by collectors of grisly border memorabilia, who lost a prize when the saloon where the jar was displayed fell to the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco. All the souvenirs Roy assembled in the back room of his own liquor emporium, they pointed out, survived well into the twentieth century, and when lumped all together fell short of that one item in value.

Lillie, reading Roy’s letters on the chintz-covered chaise in her West End flat, admired the Spencerian penmanship and ruthless prairie-school attention to vocabulary and syntax, suspecting they were transcribed but unaware of how much they had been altered from dictation. She assumed he was Canadian, and not from its wilderness; her middle-class British upbringing would countenance no origins less civilized than Toronto or Montreal. She pictured him adjudicating from a high mahogany bench in a room that resembled the inside of a gentle-man’s stud box, like Oliver Wendell Holmes in a rotogravure in The Strand.

She could not know that he presided from behind the bar in a frame shack surrounded by dry riverbeds, wrote his name only laboriously with his tongue clamped between his teeth, and was once observed consulting the big mustard-colored volume issued in Austin upside-down. When his court wasn’t in session, the book reposed either under his broad bottom or beneath the weight of a big yellow-handled Colt to accommodate the broken spine. Its pages were stained with whiskey and Levi Garrett’s, Roy’s choice of chaw, and welded together in spots, very unlike the pristine condition in which he maintained the revolver. Bruno, the tame black bear the Law West of the Pecos kept chained outside the saloon, made deep, contented rumbling noises when Roy used the muzzle to scratch him behind the ears.

But then the book was just an emblem, like the notary seal its owner employed to crack pecans when he had the misery in his fingers. The pistol, the noose, and in one instance Bruno himself made the better point in practice. The incessant hot wind did not blow from the direction of published precedent, but from the predators’ dens in the Indian Nations and the caves south in Chihuahua where bandits hid.

Roy must have cut a figura muy hermosa in the vain splendor of his youth. Any pictures that might have been struck at that time have not come down to us, but when in his December days he set aside his bung-starter gavel and straddled old Bayo, his beloved gray, for his only known form of exercise, he changed his rumpled suit of town clothes and put on a broad Mexican hat and strapped big silver rowels on his heels, gulling uninformed visitors into mistaking him for an ancient grandee. This uniform, and certain things about his conduct, suggest that in convincing himself he’d deprived the world of its most scarlet brigand, he had chosen to offer his own life in place of his victim’s, representing Joaquin as he might have looked and behaved had he survived to a crepuscular old age.

Then again, a skillful liar overlooks nothing in his effort to appear sincere.

At the time of the fabled encounter, of course, Roy was biding his time at the end of a green rope, supporting himself on his toes and waiting for one of his inexhaustible supply of sympathetic señoritas to come along and cut him down. In his eagerness to impress an actress, he superimposed Murietta on the Mexican officer he’d killed for the affections of a woman, who was by some accounts his rescuer later. (By others it was a combination of hemp rot and a stiff breeze.) A weakness for the patient sex ran through Roy Bean’s family like typhus; and a good thing, too, or our story would have no theme.

But we have a thousand miles to cover before Langtry and old Bayo, thirty years before Vinegarroon, and have still to get to the Channel Islands.

Excerpted from ROY & LILLIE by Loren D. Estleman.

Copyright © 2010 by Loren D. Estleman.

Published in 2010 by A Tom Doherty Associates Book.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

His reputation, like the lust for Stetsons and high-heeled boots, started at the state line, and he made the most of it by plastering the front of the Jersey Lilly with signs (ICE-COLD BEER & LAW WEST OF THE PECOS) and placing himself on display in a rocking chair on the porch at train time. Earlier he’d bribed conductors and porters to prime passengers for the big attraction, but the railroad men were willing enough to spread the stories free of charge, so eventually he returned his poke to his pocket. Roy was scrupulous when it came to his own money.

Pilgrims who witnessed this exhibition of living waxworks noted that physically, the man matched his legend, and assumed he was born fully fleshed out in his seventh decade, with his belly spilling through the banker’s waistcoat buttoned only at the top, tumbleweed whiskers, and eyes that glistened like damp plums under a sombrero with a buggy-wheel brim. But in his youth he was a frontier Apollo, tall and rawboned, with a bristling black beard; a land-locked Pirate Prince who shot a man in San Diego, California, over an affair of the heart and spent his period of incarceration accumulating poundage from a steady supply of cold chicken and enchiladas smuggled into his cell by pretty señoritas of the old pueblo. In Roy Bean’s universe, a pirate was never anything less than a prince and señoritas were invariably pretty.

Was this man, loose-gutted and musty-smelling, the lean young panther who’d crouched behind bars, fastidiously licking grease from his fingers and grinning at the giggling spectators outside?

“I have an old injury from a fall from my horse while serving with the U.S. Cavalry during the battle for Mexico City,” he wrote Lillie Langtry many years later, by way of one of his literate children. “The pettifoggers in Washington have held up my pension, but there is one less Spanish despot walking the earth for my effort, and that’s sufficient reward.”

He was anticipating a face-to-face meeting with the actress and the need to explain the stiff neck that had plagued him for nearly fifty years. The complaint was actually the result of a lynching that failed to take. He’d cultivated the facial hair, it was said, to mask the hemp scars. The circumstances were cloudy but had something to do with the honor of a young woman. (A pattern was forming.) It happened— if it happened— in Los Angeles, California, more than six years after the ratification of the peace treaty between the United States and Mexico.

He never defended the Union, and his subsequent attempt to bring it down at Glorieta was neglibile. In the last year of the Mexican adventure, most accounts place Roy in Independence, Missouri, with his brother Sam (who had served with the American expeditionary force below the border), arranging to join a wagon train with the intention of establishing a trading post west of the Rockies. Roy was always an entrepreneur first, a colorful character second, and a man of justice only because he refused to relinquish possession of the only book on Texas statutes for two hundred dusty miles.

If, however, he could be said to have come by anything honestly, it was his interest in the disposition of the law. Another brother, Joshua, presided over primitive San Diego as alcalde, a post that settled disputes among natives and passed sentence for capital crimes such as the theft of a neighbor’s sourdough starter. Josh, too, claimed service in Mexico, but no record ever surfaced. He stepped into the more Anglo-sounding office of mayor when American interests prevailed, and in 1850 secured an appointment as general with the California state militia, shooting claim-jumpers from the goldfields and the occasional Chinese. Subordinates with a good sense of an international play on words addressed him as “General Frijol.” As the brother of so prominent a man, Roy basked in reflected esteem, romancing girls in his fine new clothes obtained on Josh’s credit, until he suggested a shooting contest with a rival named Collins— from horse back, with each man presenting himself as the other’s target.

Collins accepted. The combatants made a few galloping passes in jousting fashion, wheeling their panting mounts and firing Paterson revolving pistols across the pommels, while spectators cheered and ducked stray rounds; the challenged party missed his challenger by a Texas mile and fell from the saddle when a ball tore through his leg. Roy drew jail time and the generosity of the Mexican girls with their cornmeal concoctions and baskets of cooked fowl. When he tired of that, his Indian drinking companions freed him with picks and shovels, to the annoyance of the judge, who was proud of the new construction of fieldstone and poured concrete. In a fit of pique he released the recovered Collins from custody.

The melodrama in Los Angeles followed. Roy wrote Lillie: “It was my privilege to slay Joaquin, the legendary highwayman, after he murdered my dear brother Joshua from ambush over a difference of principles.”

He neglected to mention that a friend of the great bandit’s had fallen out with General Frijol over the affections of a young Indian woman and had lain in wait for him with a musket.

All his long life, Roy clung to the quixotic notion that his favorite brother was one of the last victims of the great Joaquin Murietta, or at least of the road agent’s machinations behind the event. It would not do that a barefoot cobbler named Cipriano Sandoval was anything more than the instrument in the passage of a Bean, or that the affair was triggered by nothing more poetic than simple lust. Eventually he may even have come to believe that he was the slayer of Murietta, and not a company of Rangers under the command of Harry Love, a character nearly as colorful as Roy, but one who came without punchlines. Like the prehistoric hunter who wore the skin of the lion he vanquished, Roy adopted the gaudy costume of the New World Spaniard, favoring black sombreros chased with silver, embroidered waistcoats, and tight pantaloons vented at the cuffs and trimmed with bells, until age, girth, and the dignity of public office counseled a more conservative form of dress.

Roy’s only recorded brush with Joaquin was the time he failed to put in top bid for the bandit’s severed head preserved in a pickle jar— presumably as a trophy to support his claim— a failure lamented by collectors of grisly border memorabilia, who lost a prize when the saloon where the jar was displayed fell to the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco. All the souvenirs Roy assembled in the back room of his own liquor emporium, they pointed out, survived well into the twentieth century, and when lumped all together fell short of that one item in value.

Lillie, reading Roy’s letters on the chintz-covered chaise in her West End flat, admired the Spencerian penmanship and ruthless prairie-school attention to vocabulary and syntax, suspecting they were transcribed but unaware of how much they had been altered from dictation. She assumed he was Canadian, and not from its wilderness; her middle-class British upbringing would countenance no origins less civilized than Toronto or Montreal. She pictured him adjudicating from a high mahogany bench in a room that resembled the inside of a gentle-man’s stud box, like Oliver Wendell Holmes in a rotogravure in The Strand.

She could not know that he presided from behind the bar in a frame shack surrounded by dry riverbeds, wrote his name only laboriously with his tongue clamped between his teeth, and was once observed consulting the big mustard-colored volume issued in Austin upside-down. When his court wasn’t in session, the book reposed either under his broad bottom or beneath the weight of a big yellow-handled Colt to accommodate the broken spine. Its pages were stained with whiskey and Levi Garrett’s, Roy’s choice of chaw, and welded together in spots, very unlike the pristine condition in which he maintained the revolver. Bruno, the tame black bear the Law West of the Pecos kept chained outside the saloon, made deep, contented rumbling noises when Roy used the muzzle to scratch him behind the ears.

But then the book was just an emblem, like the notary seal its owner employed to crack pecans when he had the misery in his fingers. The pistol, the noose, and in one instance Bruno himself made the better point in practice. The incessant hot wind did not blow from the direction of published precedent, but from the predators’ dens in the Indian Nations and the caves south in Chihuahua where bandits hid.

Roy must have cut a figura muy hermosa in the vain splendor of his youth. Any pictures that might have been struck at that time have not come down to us, but when in his December days he set aside his bung-starter gavel and straddled old Bayo, his beloved gray, for his only known form of exercise, he changed his rumpled suit of town clothes and put on a broad Mexican hat and strapped big silver rowels on his heels, gulling uninformed visitors into mistaking him for an ancient grandee. This uniform, and certain things about his conduct, suggest that in convincing himself he’d deprived the world of its most scarlet brigand, he had chosen to offer his own life in place of his victim’s, representing Joaquin as he might have looked and behaved had he survived to a crepuscular old age.

Then again, a skillful liar overlooks nothing in his effort to appear sincere.

At the time of the fabled encounter, of course, Roy was biding his time at the end of a green rope, supporting himself on his toes and waiting for one of his inexhaustible supply of sympathetic señoritas to come along and cut him down. In his eagerness to impress an actress, he superimposed Murietta on the Mexican officer he’d killed for the affections of a woman, who was by some accounts his rescuer later. (By others it was a combination of hemp rot and a stiff breeze.) A weakness for the patient sex ran through Roy Bean’s family like typhus; and a good thing, too, or our story would have no theme.

But we have a thousand miles to cover before Langtry and old Bayo, thirty years before Vinegarroon, and have still to get to the Channel Islands.

Excerpted from ROY & LILLIE by Loren D. Estleman.

Copyright © 2010 by Loren D. Estleman.

Published in 2010 by A Tom Doherty Associates Book.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherForge Books

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0765322285

- ISBN 13 9780765322289

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 21.95

Shipping:

US$ 17.00

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Roy & Lillie: A Love Story

Published by

Forge Books

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0765322285

ISBN 13: 9780765322289

New

Hardcover

First Edition

Quantity: 2

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. Brand new out of print book. Small Publisher overstock mark on lower edge. Seller Inventory # 001212

Buy New

US$ 21.95

Convert currency