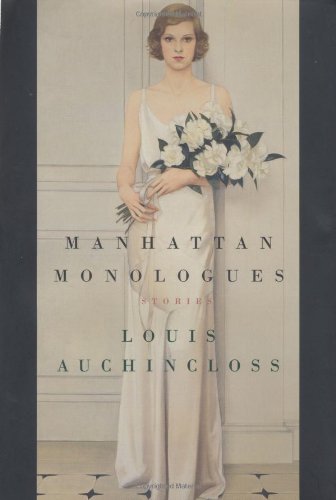

Items related to Manhattan Monologues: Stories

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

I have never dropped the junior from my name, Ambrose Vollard, even

after my father"s death, because I always felt that the important

thing about me was that I was his son. It was not that he was a

distinguished historical figure—he wasn"t. He lived the life, as my

mother once put it, of a "charming idler," the adequately endowed New

York gentleman of Knickerbocker forebears who had dedicated his

existence to sport and adventure. But he was also a hero— that was

the real point — to his non-heroic only son. As a Rough Rider he had

charged up San Juan Hill after his beloved leader, the future

President; he had slaughtered dozens of the most dangerous beasts of

the globe; and he had attended expeditions to freezing and tropical

uncharted lands for museums and zoos.

As a child I was obsessed with the notion that youth was only

a preparation for the rigors of manhood. I was fourteen when the

battleship Maine was blown up in the harbor of Havana, and I could

never forget the noisy reaction of Father and his two brothers at the

family board in Washington Square or their enthusiastic welcome of

the prospect of war. They actually hoped to see New York under fire

from the Spanish fleet, and America awakened from its slothful torpor

and materialism by the clarion call to arms! The Vollard brothers

were all tall bony men, with fine knobbly aristocratic features, who

spoke in decibels higher than anyone else"s, dominating every

conversation with their loud mocking laughs, never guilty of

any "business" but zestfully using the remnants of an old real estate

fortune in pursuit of the fox, the grizzly bear or the lion, while

not neglecting — for no Philistines they!— the reading of great books

or the viewing of great pictures or even, if they could be silent

long enough, the hearing of great music. I used to think of Father as

a kind of amiable Cesare Borgia. I looked at him with an awe

sandwiched between two dreads: the dread of never being able to

emulate him and the dread of his finding this out.

Colonel Roosevelt, as he was always referred to in the

family, even after he had received higher titles, was Father"s god as

well as friend. This great man, for all his multiple interests, had

time in his life for men like the Vollards, whose zeal and courage

and love of violent action made up, to his mind anyway, for their

social inutility. I was introduced early, not only to the Colonel but

to his books, and was indoctrinated in the creed that bravery was the

sovereign virtue in a man, that a "splendid little war" like the

Spanish one had been a blessing in disguise to preserve our national

virility and that a coward was not a man at all.

And women? What of them? Well, their role was simpler: to

inspire men and to bear children. Why, I sometimes agonized, in the

deep, dark, deluding safety of the night, had I not been born a

woman? And I knew, I always knew, that the mere presence of this evil

wish, even in the innermost recesses of my mind, damned me forever.

At least with men. Was there any hope of redemption in the eyes of

women? Did Mother suspect what I was going through? I sometimes

wondered.

Leonie Vollard was as small and white and quiet as her

husband was big and brown and noisy, but she was in no way

subservient. Despite their obvious deep devotion to each other, they

nonetheless preserved inviolate their respective and distinctly

separate "spheres of interest." She never protested against his long

absences on hunting and exploratory expeditions, nor did he ever

interfere with her exquisite housekeeping in the lovely red-brick

early Federal house in Washington Square. She sat silently through

the spirited, even raucous arguments of the Vollard clan at her

dinner table, and he was a subdued guest at the readings of her

poetry club. In his den he was allowed any number of animal trophies,

but no claw, hoof, horn or antler was permitted in her chaste blue-

and-yellow parlor. Similarly, the children were divided; my two

younger sisters were left largely to their mother"s care and

supervision, while my guidance and training were Father"s primary

responsibilities. Yet Mother never conveyed any impression that she

was unconcerned with my welfare. Quiet and reserved as she was, she

managed to radiate the feeling that every unit of her family was

equally important to her.

Certainly the thing that confused me most in my relationship

with Father was that he was the most amiable, the most enchanting

parent one could imagine. Of course, that had to be because he had no

conception of what was going on inside me. His patient joviality in

teaching me to ride, to jump, to shoot and to hunt, first the

pheasant and then the fox, on our Long Island estate was never marred

by reprehension of my ineptitudes, but loudly expressed by applause

at my every successful effort. And in due time I learned to conduct

myself with some competence in riding and shooting, aided by my

earnest desire to accomplish the seemingly hopeless task of becoming

the youth Father cheerfully insisted on believing I was. To follow

his graceful figure across the fields after the hounds was indeed a

pleasure, but I never lost sight of what to me were the inevitable

future tests of manhood that I believed awaited me as the real

justification for my training: that war where I would have to fight

an enemy, perhaps hand to hand, in mud and horror, or the African

safari where I would be obliged to stand rigid before a charging

rhino.

At Saint Jude"s, the boys" boarding school in Massachusetts

to which I was sent, I was slightly more relaxed, relieved as I was,

except on parents" weekends, of Father"s pushing-me-on presence,

although the academy heartily endorsed his athletic enthusiasms,

including football, a game I particularly detested. Father went so

far as to say that he would be ashamed of any son or nephew who

didn"t go in for the game. I was tall for my age but slender, and I

got knocked about on the field quite painfully, yet I survived, and

not too discreditably. Father, who came up to school frequently to

view the Saturday afternoon games, was aware of my difficulty and did

his best to reassure me. Walking back to the gymnasium after a match,

he put an arm around my shoulders and said: "You mustn"t mind, dear

boy, if you don"t make the school varsity team. A man can do just so

much with the physique God has given him, and you"ve done everything

that could be expected of a boy with your muscular equipment. I am

very proud of you. In a couple of years you may become heftier, but

it doesn"t matter, because you"ll always do the best with what you"ve

got, and that"s all that can be expected of any man."

Oh, yes, he made allowances; he always did for me. He was

determined to squeeze me somehow into his male heaven. But in the

fall of my next-to-last year at the school I came close, for the

first time in my life, to something faintly resembling an outer

protest against Saint Jude"s echo of Father"s principles. This new

little spurt of defiance was no doubt fostered by Father"s absence,

not only from the school but the country on an extended expedition to

the Antarctic.

I began, at first surreptitiously, to skip the near

compulsory attendance at the Saturday afternoon football matches

between Saint Jude"s and visiting teams. This was considered a

serious breach of the required "school spirit," and when it became

known that I had been caught in the library during our match with

Chelton, the supreme athletic contest of the school year, I was

shocked to find myself condemned to the humiliation of being "pumped."

This grave punishment of a graver offense consisted of being

ordered to stand up before the whole school at roll call to be

berated by the senior monitor (no faculty being present, as if to

emphasize the hors la loi aspect of the proceeding) and then to be

hustled by six sturdy members of the senior class down to the cellar

to be half-drowned in the laundry wash basin.

The actual experience was soon over, but the shame was

supposed to be deep and lasting. Yet I was oddly unmindful of the

social ostracism that followed the event. It was something of a

relief to be known at last for the poor thing I was. My only real

concern was what Father would think. Would he even hear of it? I

madly hoped not.

Of course he did, and from the headmaster himself in a

special report to my parents. Home from the South Pole, he came right

up to the school and took me for a Sunday afternoon walk through the

woods to the river. It was a gloomy day, cold and cloudy, and I felt

as bare as the stripped November trees. But the pain and concern on

poor Father"s face and the gentleness of his tone took me at last out

of myself, and my mind turned over feverishly, seeking a way to spare

his feelings.

"But what was your point, dear boy, in absenting yourself

from the games? Was it to have more time to study?"

"Oh, no."

"Was it possibly to be alone to do something that was

prohibited? Like smoking or drinking? You needn"t be afraid that your

old father will give you away. I"m just trying to understand; that"s

all."

And then I had it! It was a desperate try, but it was all I

had. "I wanted to test my courage! I wanted to see if I could stand

up to the worst thing that could happen to me in school! I wanted to

be pumped!"

Of course, this was a bare-faced lie. I had had no notion

that I would be caught or, if caught, that I would be so severely

punished. But Father"s face, though bewildered, was clearing, and I

hurried on. "Boys my age haven"t had the chance to prove themselves

the way you did in the Spanish war! I wanted to see how I would stand

up in a crisis. And I did! I did!"

Father had tears in his eyes as he turned to hug me. "Oh, my

dear fellow, you went much too far! I"m afraid I"ve done too much

bragging about my own tiny feats. What have I ever done but kill a

few animals?"

"And men," I added stoutly.

"Well, we have to do that in war, regrettably. But, dear son,

you must learn to moderate yourself. You have to live in this world,

and that involves a certain amount of compromise. Not of your honor,

of course, but in small social matters such as attending popular

events, even if they bore you. One mustn"t let oneself get too

prickly. And as for courage, dear boy, you have as much of it as any

proud father could wish!"

My next real nervous crisis was delayed by four years. After

my sophomore year at Harvard, Father took me along on what I had

always regarded as the inevitable test—a hunting safari in Kenya.

Mother and my sisters, of course, were left behind in the enviable

security of New York; it was only I who had to be exposed to what

Father gleefully assured me would be the thrill of my lifetime.

We set forth into the veldt with one of my uncles and a

couple of enthusiastic young male cousins, a white hunter and some

thirty bearers (the Vollard men always did things poshly). I had,

reluctantly, to admit that I liked the countryside. It rolled away

romantically and awesomely to the horizon on all sides, and had it

been stripped of animal and insect life, I could have imagined

enjoying myself. But of course it fairly teemed with both, and my

relatives were intent on seeking the largest and most dangerous of

the fauna. They soon found them.

The days were bad enough, with a charging elephant or Cape

buffalo or lion brought down by Vollard fire two or three times a

week, but the nights were worse. Our white hunter assured me that the

great beasts that wandered through our camp at night would never

break into a tent, but how could I be sure of that? Why would the

mate of an elephant slaughtered in daylight not take revenge on its

helpless murderers in the dark? I would toss on my cot for hours

until sheer exhaustion robbed me of consciousness. And the huge bugs!

Ugh!

Father noticed that I was tired, and sometimes he mercifully

left me in camp to rest while the others were out shooting. But even

then I would be nervous, left alone with a few unarmed bearers while

animals prowled around and the guns were away. When I went out with

them, Father usually kept me at his side, and he was noisily

congratulatory when I shot and killed an oryx and then an eland.

Neither of the poor beasts had tried to do anything but get away from

us. And we were blessedly approaching the end of our terrible safari

when the moment that I had dreaded burst upon me. Our hunter had

spotted a huge old tuskless—and hence dangerously malevolent —bull

elephant, exiled from the herd and surly, and Father suggested that

he and I should, without the others, have the glory of bringing it

down.

As we cautiously approached the monster, it picked up our

scent and turned to us, raising its trunk formidably and flapping its

great ears. Even Father seemed to have a second thought.

"Ambrose, quick! Run back to the others; I can handle this."

And I would have done so! I would! But I was literally

paralyzed with panic. My legs were two stone pillars; I couldn"t even

raise my rifle. The bull was charging now, a thundering black cloud

of terror, and I knew my end had come.

I heard the crack of Father"s gun, and the huge beast went

down, a rolling mass of agony, then suddenly still.

"By God, you"re a cool one!" Father cried. "You stood there

without blinking. And you were a gentleman, too. You let me have the

first go at him when there mightn"t have been a second!"

"Oh, I knew you"d bring him down," I heard myself say.

That night I was struck with a fever, which nobody attributed

to my trauma, and I was sent back to the base camp. By the time I had

recuperated, the safari was over.

The next decade brought great changes and something like peace to my

life. In the first place, Father lost the greater part of his by then

diminished fortune when the Knickerbocker Trust Company closed its

doors in the panic of 1907. There was no longer the possibility of my

leading the economically carefree life that he and his brothers had

enjoyed; it was now incumbent upon me to earn my own living, which

fortunately I was not only happy but relieved to do. After Harvard

College, I attended Harvard Law and then secured a good position as a

clerk in a leading Wall Street firm.

Father was constantly apologetic that his poor management had

condemned me to what he downrated as the passive life of a desk grub.

But to me it was the pleasant calm of a dull gray restful heaven

after the flickering red of adventure. I believed that my fears and

anticipations were over, that I had been tested, after all, and not

found wanting as a man, and that I could now look forward, like

millions of other males, to the routine of a mild usefulness. To cap

it all, I married a girl who had the same ambition—or lack of it, as

the Vollards undoubtedly would have put it.

Ellen, the child of Long Island neighbors whom I had known

and liked since childhood, had always been a quiet little girl, sober

and serious, who from her earliest days had known exactly what she

wanted from life: a f...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2002

- ISBN 10 061815289X

- ISBN 13 9780618152896

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages226

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 5.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. my shelf location - so-h-52*. Seller Inventory # 240229020

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new061815289X

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_061815289X

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.58. Seller Inventory # 061815289X-2-1

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.58. Seller Inventory # 353-061815289X-new

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. First Edition. 1st Edition. A FINE Hardcover with a FINE dustjacket. AS NEW. All dustjackets wrapped in Archival protection, and delivery confirmation with all our orders!. Seller Inventory # OF4-358

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. First Edition. A collection of short tales features characters from society's upper crust who struggle with their consciences, from "All That May Become a Man" in which Ambrose struggles with parental expectations, to "The Heiress," which follows Aggie, who chooses between true love and a marriage of convenience. 10,000 first printing. Seller Inventory # DADAX061815289X

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard061815289X

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think061815289X

Manhattan Monologues: Stories

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover061815289X